HOW ESAU AND JACOB, ISAAC'S SONS DIVIDED THEIR HABITATION; AND ESAU POSSESSED IDUMEA AND JACOB CANAAN

AFTER the death of Isaac, his sons divided their habitations respectively; nor did they retain what they had before; but Esau departed from the city of Hebron, and left it to his brother, and dwelt in Seir, and ruled over Idumea. He called the country by that name from himself, for he was named Adom; which appellation he got on the following occasion : - One day returning from the toil of hunting very hungry, (it was when he was a child in age,) he lighted on his brother when he was getting ready lentile-pottage for his dinner, which was of a very red color; on which account he the more earnestly longed for it, and desired him to give him some of it to eat: but he made advantage of his brother's hunger, and forced him to resign up to him his birthright; and he, being pinched with famine, resigned it up to him, under an oath. Whence it came, that, on account of the redness of this pottage, he was, in way of jest, by his contemporaries, called Adom, for the Hebrews call what is red Adom; and this was the name given to the country; but the Greeks gave it a more agreeable pronunciation, and named it Idumea.

He became the father of five sons; of whom Jaus, and Jalomus, and Coreus, were by one wife, whose name was Alibama; but of the rest, Aliphaz was born to him by Ada, and Raguel by Basemmath: and these were the sons of Esau. Aliphaz had five legitimate sons; Theman, Omer, Saphus, Gotham, and Kanaz; for Amalek was not legitimate, but by a concubine, whose name was Thamna. These dwelt in that part of Idumea which is called Gebalitis, and that denominated from Amalek, Amalekitis; for Idumea was a large country, and did then preserve the name of the whole, while in its several parts it kept the names of its peculiar inhabitants

HOW JOSEPH, THE YOUNGEST OF JACOB'S SONS, WAS ENVIED BY HIS BRETHREN, WHEN CERTAIN DREAMS HAD FORESHOWN HIS FUTURE HAPPINESS

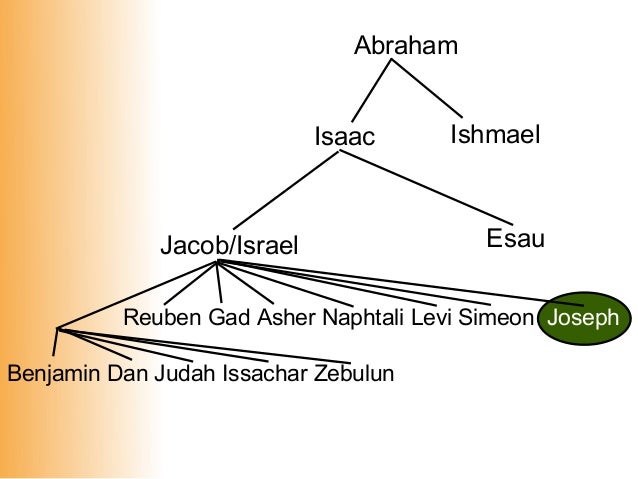

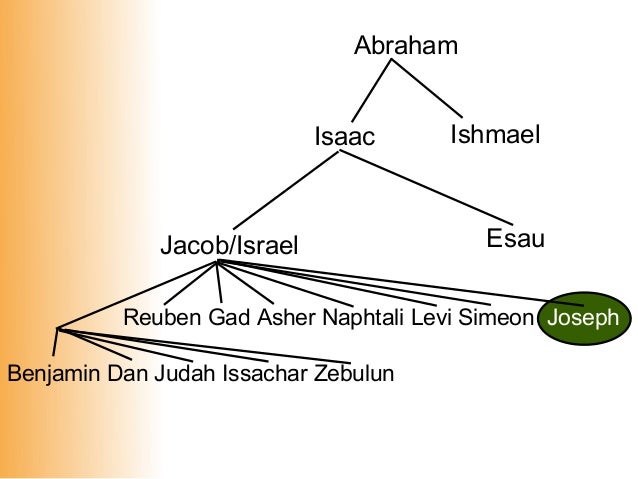

i T happened that Jacob came to so great happiness as rarely any other person had arrived at. He was richer than the rest of the inhabitants of that country; and was at once envied and admired for such virtuous sons, for they were deficient in nothing, but were of great souls, both for laboring with their hands and enduring of toil; and shrewd also in understanding. And God exercised such a providence over him, and such a care of his happiness, as to bring him the greatest blessings, even out of what appeared to be the most sorrowful condition; and to make him the cause of our forefathers' departure out of Egypt, him and his posterity. The occasion was this : - When Jacob had his son Joseph born to him by Rachel, his father loved him above the rest of his sons, both because of the beauty of his body, and the virtues of his mind, for he excelled the rest in prudence. This affection of his father excited the envy and the hatred of his brethren; as did also his dreams which he saw, and related to his father, and to them, which foretold his future happiness, it being usual with mankind to envy their very nearest relations such their prosperity. Now the visions which Joseph saw in his sleep were these

When they were in the middle of harvest, and Joseph was sent by his father, with his brethren, to gather the fruits of the earth, he saw a vision in a dream, but greatly exceeding the customary appearances that come when we are asleep; which, when he was got up, he told his brethren, that they might judge what it portended. He said, he saw the last night, that his wheat-sheaf stood still in the place where he set it, but that their sheaves ran to bow down to it, as servants bow down to their masters. But as soon as they perceived the vision foretold that he should obtain power and great wealth, and that his power should be in opposition to them, they gave no interpretation of it to Joseph, as if the dream were not by them undestood: but they prayed that no part of what they suspected to be its meaning might come to pass; and they bare a still greater hatred to him on that account.

But God, in opposition to their envy, sent a second vision to Joseph, which was much more wonderful than the former; for it seemed to him that the sun took with him the moon, and the rest of the stars, and came down to the earth, and bowed down to him. He told the vision to his father, and that, as suspecting nothing of ill-will from his brethren, when they were there also, and desired him to interpret what it should signify. Now Jacob was pleased with the dream: for, considering the prediction in his mind, and shrewdly and wisely guessing at its meaning, he rejoiced at the great things thereby signified, because it declared the future happiness of his son; and that, by the blessing of God, the time would come when he should be honored, and thought worthy of worship by his parents and brethren, as guessing that the moon and sun were like his mother and father; the former, as she that gave increase and nourishment to all things; and the latter, he that gave form and other powers to them; and that the stars were like his brethren, since they were eleven in number, as were the stars that receive their power from the sun and moon

And thus did Jacob make a judgment of this vision, and that a shrewd one also. But these interpretations caused very great grief to Joseph's brethren; and they were affected to him hereupon as if he were a certain stranger, that was to those good things which were signified by the dreams and not as one that was a brother, with whom it was probable they should be joint-partakers; and as they had been partners in the same parentage, so should they be of the same happiness. They also resolved to kill the lad; and having fully ratified that intention of theirs, as soon as their collection of the fruits was over, they went to Shechem, which is a country good for feeding of cattle, and for pasturage; there they fed their flocks, without acquainting their father with their removal thither; whereupon he had melancholy suspicions about them, as being ignorant of his sons' condition, and receiving no messenger from the flocks that could inform him of the true state they were in; so, because he was in great fear about them, he sent Joseph to the flocks, to learn the circumstances his brethren were in, and to bring him word how they did.

=====================================

HOW JOSEPH WAS THUS SOLD BY HIS BRETHREN INTO EGYPT, BY REASON OF THEIR HATRED TO HIM; AND HOW HE THERE GREW FAMOUS AND ILLUSTRIOUS AND HAD HIS BRETHREN UNDER HIS POWER.

NOW these brethren rejoiced as soon as they saw their brother coming to them, not indeed as at the presence of a near relation, or as at the presence of one sent by their father, but as at the presence of an enemy, and one that by Divine Providence was delivered into their hands; and they already resolved to kill him, and not let slip the opportunity that lay before them. But when Reubel, the eldest of them, saw them thus disposed, and that they had agreed together to execute their purpose, he tried to restrain them, showing them the heinous enterprise they were going about, and the horrid nature of it; that this action would appear wicked in the sight of God, and impious before men, even though they should kill one not related to them; but much more flagitious and detestable to appear to have slain their own brother, by which act the father must be treated unjustly in the son's slaughter, and the mother (1) also be in perplexity while she laments that her son is taken away from her, and this not in a natural way neither. So he entreated them to have a regard to their own consciences, and wisely to consider what mischief would betide them upon the death of so good a child, and their youngest brother; that they would also fear God, who was already both a spectator and a witness of the designs they had against their brother; that he would love them if they abstained from this act, and yielded to repentance and amendment; but in case they proceeded to do the fact, all sorts of punishments would overtake them from God for this murder of their brother, since they polluted his providence, which was every where present, and which did not overlook what was done, either in deserts or in cities; for wheresoever a man is, there ought he to suppose that God is also. He told them further, that their consciences would be their enemies, if they attempted to go through so wicked an enterprise, which they can never avoid, whether it be a good conscience; or whether it be such a one as they will have within them when once they have killed their brother. He also added this besides to what he had before said, that it was not a righteous thing to kill a brother, though he had injured them; that it is a good thing to forget the actions of such near friends, even in things wherein they might seem to have offended; but that they were going to kill Joseph, who had been guilty of nothing that was ill towards them, in whose case the infirmity of his small age should rather procure him mercy, and move them to unite together in the care of his preservation. That the cause of killing him made the act itself much worse, while they determined to take him off out of envy at his future prosperity, an equal share of which they would naturally partake while he enjoyed it, since they were to him not strangers, but the nearest relations, for they might reckon upon what God bestowed upon Joseph as their own; and that it was fit for them to believe, that the anger of God would for this cause be more severe upon them, if they slew him who was judged by God to be worthy of that prosperity which was to be hoped for; and while, by murdering him, they made it impossible for God to bestow it upon him.

ReubN said these and many other things, and used entreaties to them, and thereby endeavored to divert them from the murder of their brother. But when he saw that his discourse had not mollified them at all, and that they made haste to do the fact, he advised them to alleviate the wickedness they were going about, in the manner of taking Joseph off; for as he had exhorted them first, when they were going to revenge themselves, to be dissuaded from doing it; so, since the sentence for killing their brother had prevailed, he said that they would not, however, be so grossly guilty, if they would be persuaded to follow his present advice, which would include what they were so eager about, but was not so very bad, but, in the distress they were in, of a lighter nature. He begged of them, therefore, not to kill their brother with their own hands, but to cast him into the pit that was hard by, and so to let him die; by which they would gain so much, that they would not defile their own hands with his blood. To this the young men readily agreed; so Reuben took the lad and tied him to a cord, and let him down gently into the pit, for it had no water at all in it; who, when he had done this, went his way to seek for such pasturage as was fit for feeding his flocks

But Judah, being one of Jacob's sons also, seeing some Arabians, of the posterity of Ismael, carrying spices and Syrian wares out of the land of Gilead to the Egyptians, after Rubel was gone, advised his brethren to draw Joseph out of the pit, and sell him to the Arabians; for if he should die among strangers a great way off, they should be freed from this barbarous action. This, therefore, was resolved on; so they drew Joseph up out of the pit, and sold him to the merchants for twenty pounds (2) He was now seventeen years old. But Reubel, coming in the night-time to the pit, resolved to save Joseph, without the privity of his brethren; and when, upon his calling to him, he made no answer, he was afraid that they had destroyed him after he was gone; of which he complained to his brethren; but when they had told him what they had done, Reubel left off his mourning.

When Joseph's brethren had done thus to him, they considered what they should do to escape the suspicions of their father. Now they had taken away from Joseph the coat which he had on when he came to them at the time they let him down into the pit; so they thought proper to tear that coat to pieces, and to dip it into goats' blood, and then to carry it and show it to their father, that he might believe he was destroyed by wild beasts. And when they had so done, they came to the old man, but this not till what had happened to his son had already come to his knowledge. Then they said that they had not seen Joseph, nor knew what mishap had befallen him; but that they had found his coat bloody and torn to pieces, whence they had a suspicion that he had fallen among wild beasts, and so perished, if that was the coat he had on when he came from home. Now Jacob had before some better hopes that his son was only made a captive; but now he laid aside that notion, and supposed that this coat was an evident argument that he was dead, for he well remembered that this was the coat he had on when he sent him to his brethren; so he hereafter lamented the lad as now dead, and as if he had been the father of no more than one, without taking any comfort in the rest; and so he was also affected with his misfortune before he met with Joseph's brethren, when he also conjectured that Joseph was destroyed by wild beasts. He sat down also clothed in sackcloth and in heavy affliction, insomuch that he found no ease when his sons comforted him, neither did his pains remit by length of time.

CONCERNING THE SIGNAL CHASTITY OF JOSEPH

NOW Potiphar, an Egyptian, who was chief cook to king Pharaoh, bought Joseph of the merchants, who sold him to him. He had him in the greatest honor, and taught him the learning that became a free man, and gave him leave to make use of a diet better than was allotted to slaves. He intrusted also the care of his house to him. So he enjoyed these advantages, yet did not he leave that virtue which he had before, upon such a change of his condition; but he demonstrated that wisdom was able to govern the uneasy passions of life, in such as have it in reality, and do not only put it on for a show, under a present state of prosperity.

For when his master's wife was fallen in love with him, both on account of his beauty of body, and his dexterous management of affairs; and supposed, that if she should make it known to him, she could easily persuade him to come and lie with her, and that he would look upon it as a piece of happy fortune that his mistress should entreat him, as regarding that state of slavery he was in, and not his moral character, which continued after his condition was changed. So she made known her naughty inclinations, and spake to him about lying with her. However, he rejected her entreaties, not thinking it agreeable to religion to yield so far to her, as to do what would tend to the affront and injury of him that purchased him, and had vouchsafed him so great honors. He, on the contrary, exhorted her to govern that passion; and laid before her the impossibility of her obtaining her desires, which he thought might be conquered, if she had no hope of succeeding; and he said, that as to himself, he would endure any thing whatever before he would be persuaded to it; for although it was fit for a slave, as he was, to do nothing contrary to his mistress, he might well be excused in a case where the contradiction was to such sort of commands only. But this opposition of Joseph, when she did not expect it, made her still more violent in her love to him; and as she was sorely beset with this naughty passion, so she resolved to compass her design by a second attempt.

When, therefore, there was a public festival coming on, in which it was the custom for women to come to the public solemnity; she pretended to her husband that she was sick, as contriving an opportunity for solitude and leisure, that she might entreat Joseph again. Which opportunity being obtained, she used more kind words to him than before; and said that it had been good for him to have yielded to her first solicitation, and to have given her no repulse, both because of the reverence he ought to bear to her dignity who solicited him, and because of the vehemence of her passion, by which she was forced though she were his mistress to condescend beneath her dignity; but that he may now, by taking more prudent advice, wipe off the imputation of his former folly; for whether it were that he expected the repetition of her solicitations she had now made, and that with greater earnestness than before, for that she had pretended sickness on this very account, and had preferred his conversation before the festival and its solemnity; or whether he opposed her former discourses, as not believing she could be in earnest; she now gave him sufficient security, by thus repeating her application, that she meant not in the least by fraud to impose upon him; and assured him, that if he complied with her affections, he might expect the enjoyment of the advantages he already had; and if he were submissive to her, he should have still greater advantages; but that he must look for revenge and hatred from her, in case he rejected her desires, and preferred the reputation of chastity before his mistress; for that he would gain nothing by such procedure, because she would then become his accuser, and would falsely pretend to her husband, that he had attempted her chastity; and that Potiphar would hearken to her words rather than to his, let his be ever so agreeable to the truth.

When the woman had said thus, and even with tears in her eyes, neither did pity dissuade Joseph from his chastity, nor did fear compel him to a compliance with her; but he opposed her solicitations, and did not yield to her threatenings, and was afraid to do an ill thing, and chose to undergo the sharpest punishment rather than to enjoy his present advantages, by doing what his own conscience knew would justly deserve that he should die for it. He also put her in mind that she was a married woman, and that she ought to cohabit with her husband only; and desired her to suffer these considerations to have more weight with her than the short pleasure of lustful dalliance, which would bring her to repentance afterwards, would cause trouble to her, and yet would not amend what had been done amiss. He also suggested to her the fear she would be in lest they should be caught; and that the advantage of concealment was uncertain, and that only while the wickedness was not known [would there be any quiet for them]; but that she might have the enjoyment of her husband's company without any danger. And he told her, that in the company of her husband she might have great boldness from a good conscience, both before God and before men. Nay, that she would act better like his mistress, and make use of her authority over him better while she persisted in her chastity, than when they were both ashamed for what wickedness they had been guilty of; and that it is much better to a life, well and known to have been so, than upon the hopes of the concealment of evil practices.

Joseph, by saying this, and more, tried to restrain the violent passion of the woman, and to reduce her affections within the rules of reason; but she grew more ungovernable and earnest in the matter; and since she despaired of persuading him, she laid her hands upon him, and had a mind to force him. But as soon as Joseph had got away from her anger, leaving also his garment with her, for he left that to her, and leaped out of her chamber, she was greatly afraid lest he should discover her lewdness to her husband, and greatly troubled at the affront he had offered her; so she resolved to be beforehand with him, and to accuse Joseph falsely to Potiphar, and by that means to revenge herself on him for his pride and contempt of her; and she thought it a wise thing in itself, and also becoming a woman, thus to prevent his accusation. Accordingly she sat sorrowful and in confusion, framing herself so hypocritically and angrily, that the sorrow, which was really for her being disappointed of her lust, might appear to be for the attempt upon her chastity; so that when her husband came home, and was disturbed at the sight of her and inquired what was the cause of the disorder she was in, she began to accuse Joseph: and, "O husband," said she, "mayst thou not live a day longer if thou dost not punish the wicked slave who has desired to defile thy bed; who has neither minded who he was when he came to our house, so as to behave himself with modesty; nor has he been mindful of what favors he had received from thy bounty (as he must be an ungrateful man indeed, unless he, in every respect, carry himself in a manner agreeable to us): this man, I say, laid a private design to abuse thy wife, and this at the time of a festival, observing when thou wouldst be absent. So that it now is clear that his modesty, as it appeared to be formerly, was only because of the restraint he was in out of fear of thee, but that he was not really of a good disposition. This has been occasioned by his being advanced to honor beyond what he deserved, and what he hoped for; insomuch that he concluded, that he who was deemed fit to be trusted with thy estate and the government of thy family, and was preferred above thy eldest servants, might be allowed to touch thy wife also." Thus when she had ended her discourse, she showed him his garment, as if he then left it with her when he attempted to force her. But Potiphar not being able to disbelieve what his wife's tears showed, and what his wife said, and what he saw himself, and being seduced by his love to his wife, did not set himself about the examination of the truth; but taking it for granted that his wife was a modest woman, and condemning Joseph as a wicked man, he threw him into the malefactors' prison; and had a still higher opinion of his wife, and bare her witness that she was a woman of a becoming modesty and chastity.

WHAT THINGS BEFELL JOSEPH IN PRISON.

NOW Joseph, commending all his affairs to God, did not betake himself to make his defense, nor to give an account of the exact circumstances of the fact, but silently underwent the bonds and the distress he was in, firmly believing that God, who knew the cause of his affliction, and the truth of the fact, would be more powerful than those that inflicted the punishments upon him : - a proof of whose providence he quickly received; for the keeper of the prison taking notice of his care and fidelity in the affairs he had set him about, and the dignity of his countenance, relaxed his bonds, and thereby made his heavy calamity lighter, and more supportable to him. He also permitted him to make use of a diet better than that of the rest of the prisoners. Now, as his fellow prisoners, when their hard labors were over, fell to discoursing one among another, as is usual in such as are equal sufferers, and to inquire one of another what were the occasions of their being condemned to a prison: among them the king's cupbearer, and one that had been respected by him, was put in bonds, upon the king's anger at him. This man was under the same bonds with Joseph, and grew more familiar with him; and upon his observing that Joseph had a better understanding than the rest had, he told him of a dream he had, and desired he would interpret its meaning, complaining that, besides the afflictions he underwent from the king, God did also add to him trouble from his dreams.

He therefore said, that in his sleep he saw three clusters of grapes hanging upon three branches of a vine, large already, and ripe for gathering; and that he squeezed them into a cup which the king held in his hand; and when he had strained the wine, he gave it to the king to drink, and that he received it from him with a pleasant countenance. This, he said, was what he saw; and he desired Joseph, that if he had any portion of understanding in such matters, he would tell him what this vision foretold. Who bid him be of good cheer, and expect to be loosed from his bonds in three days' time, because the king desired his service, and was about to restore him to it again; for he let him know that God bestows the fruit of the vine upon men for good; which wine is poured out to him, and is the pledge of fidelity and mutual confidence among men; and puts an end to their quarrels, takes away passion and grief out of the minds of them that use it, and makes them cheerful. "Thou sayest that thou didst squeeze this wine from three clusters of grapes with thine hands, and that the king received it: know, therefore, that this vision is for thy good, and foretells a release from thy present distress within the same number of days as the branches had whence thou gatheredst thy grapes in thy sleep. However, remember what prosperity I have foretold thee when thou hast found it true by experience; and when thou art in authority, do not overlook us in this prison, wherein thou wilt leave us when thou art gone to the place we have foretold; for we are not in prison for any crime; but for the sake of our virtue and sobriety are we condemned to suffer the penalty of malefactors, and because we are not willing to injure him that has thus distressed us, though it were for our own pleasure." The cupbearer, therefore, as was natural to do, rejoiced to hear such an interpretation of his dream, and waited the completion of what had been thus shown him beforehand

But another servant there was of the king, who had been chief baker, and was now bound in prison with the cupbearer; he also was in good hope, upon Joseph's interpretation of the other's vision, for he had seen a dream also; so he desired that Joseph would tell him what the visions he had seen the night before might mean. They were these that follow: - "Methought," says he, "I carried three baskets upon my head; two were full of loaves, and the third full of sweetmeats and other eatables, such as are prepared for kings; but that the fowls came flying, and eat them all up, and had no regard to my attempt to drive them away." And he expected a prediction like to that of the cupbearer. But Joseph, considering and reasoning about the dream, said to him, that he would willingly be an interpreter of good events to him, and not of such as his dream denounced to him; but he told him that he had only three days in all to live, for that the [three] baskets signify, that on the third day he should be crucified, and devoured by fowls, while he was not able to help himself. Now both these dreams had the same several events that Joseph foretold they should have, and this to both the parties; for on the third day before mentioned, when the king solemnized his birth-day, he crucified the chief baker, but set the butler free from his bonds, and restored him to his former ministration.

But God freed Joseph from his confinement, after he had endured his bonds two years, and had received no assistance from the cupbearer, who did not remember what he had said to him formerly; and God contrived this method of deliverance for him. Pharaoh the king had seen in his sleep the same evening two visions; and after them had the interpretations of them both given him. He had forgotten the latter, but retained the dreams themselves. Being therefore troubled at what he had seen, for it seemed to him to be all of a melancholy nature, the next day he called together the wisest men among the Egyptians, desiring to learn from them the interpretation of his dreams. But when they hesitated about them, the king was so much the more disturbed. And now it was that the memory of Joseph, and his skill in dreams, came into the mind of the king's cupbearer, when he saw the confusion that Pharaoh was in; so he came and mentioned Joseph to him, as also the vision he had seen in prison, and how the event proved as he had said; as also that the chief baker was crucified on the very same day; and that this also happened to him according to the interpretation of Joseph. That Joseph himself was laid in bonds by Potiphar, who was his head cook, as a slave; but, he said, he was one of the noblest of the stock of the Hebrews; and said further, his father lived in great splendor. "If, therefore, thou wilt send for him, and not despise him on the score of his misfortunes, thou wilt learn what thy dreams signify." So the king commanded that they should bring Joseph into his presence; and those who received the command came and brought him with them, having taken care of his habit, that it might be decent, as the king had enjoined them to do.

But the king took him by the hand; and, "O young man," says he, "for my servant bears witness that thou art at present the best and most skillful person I can consult with; vouchsafe me the same favors which thou bestowedst on this servant of mine, and tell me what events they are which the visions of my dreams foreshow; and I desire thee to suppress nothing out of fear, nor to flatter me with lying words, or with what may please me, although the truth should be of a melancholy nature. For it seemed to me that, as I walked by the river, I saw kine fat and very large, seven in number, going from the river to the marshes; and other kine of the same number like them, met them out of the marshes, exceeding lean and ill-favored, which ate up the fat and the large kine, and yet were no better than before, and not less miserably pinched with famine. After I had seen this vision, I awaked out of my sleep; and being in disorder, and considering with myself what this appearance should be, I fell asleep again, and saw another dream, much more wonderful than the foregoing, which still did more affright and disturb me: - I saw seven ears of corn growing out of one root, having their heads borne down by the weight of the grains, and bending down with the fruit, which was now ripe and fit for reaping; and near these I saw seven other ears of corn, meager and weak, for want of rain, which fell to eating and consuming those that were fit for reaping, and put me into great astonishment."

To which Joseph replied: - "This dream," said he, "O king, although seen under two forms, signifies one and the same event of things; for when thou sawest the fat kine, which is an animal made for the plough and for labor, devoured by the worser kine, and the ears of corn eaten up by the smaller ears, they foretell a famine, and want of the fruits of the earth for the same number of years, and equal with those when Egypt was in a happy state; and this so far, that the plenty of these years will be spent in the same number of years of scarcity, and that scarcity of necessary provisions will be very difficult to be corrected; as a sign whereof, the ill-favored kine, when they had devoured the better sort, could not be satisfied. But still God foreshows what is to come upon men, not to grieve them, but that, when they know it beforehand, they may by prudence make the actual experience of what is foretold the more tolerable. If thou, therefore, carefully dispose of the plentiful crops which will come in the former years, thou wilt procure that the future calamity will not be felt by the Egyptians."

To which Joseph replied: - "This dream," said he, "O king, although seen under two forms, signifies one and the same event of things; for when thou sawest the fat kine, which is an animal made for the plough and for labor, devoured by the worser kine, and the ears of corn eaten up by the smaller ears, they foretell a famine, and want of the fruits of the earth for the same number of years, and equal with those when Egypt was in a happy state; and this so far, that the plenty of these years will be spent in the same number of years of scarcity, and that scarcity of necessary provisions will be very difficult to be corrected; as a sign whereof, the ill-favored kine, when they had devoured the better sort, could not be satisfied. But still God foreshows what is to come upon men, not to grieve them, but that, when they know it beforehand, they may by prudence make the actual experience of what is foretold the more tolerable. If thou, therefore, carefully dispose of the plentiful crops which will come in the former years, thou wilt procure that the future calamity will not be felt by the Egyptians."

================================

isaac http://www.ccel.org/j/josephus/works/ant-2.htm

Flavius Josephus

http://www.ccel.org/j/josephus/works/ant-2.htm

===================================